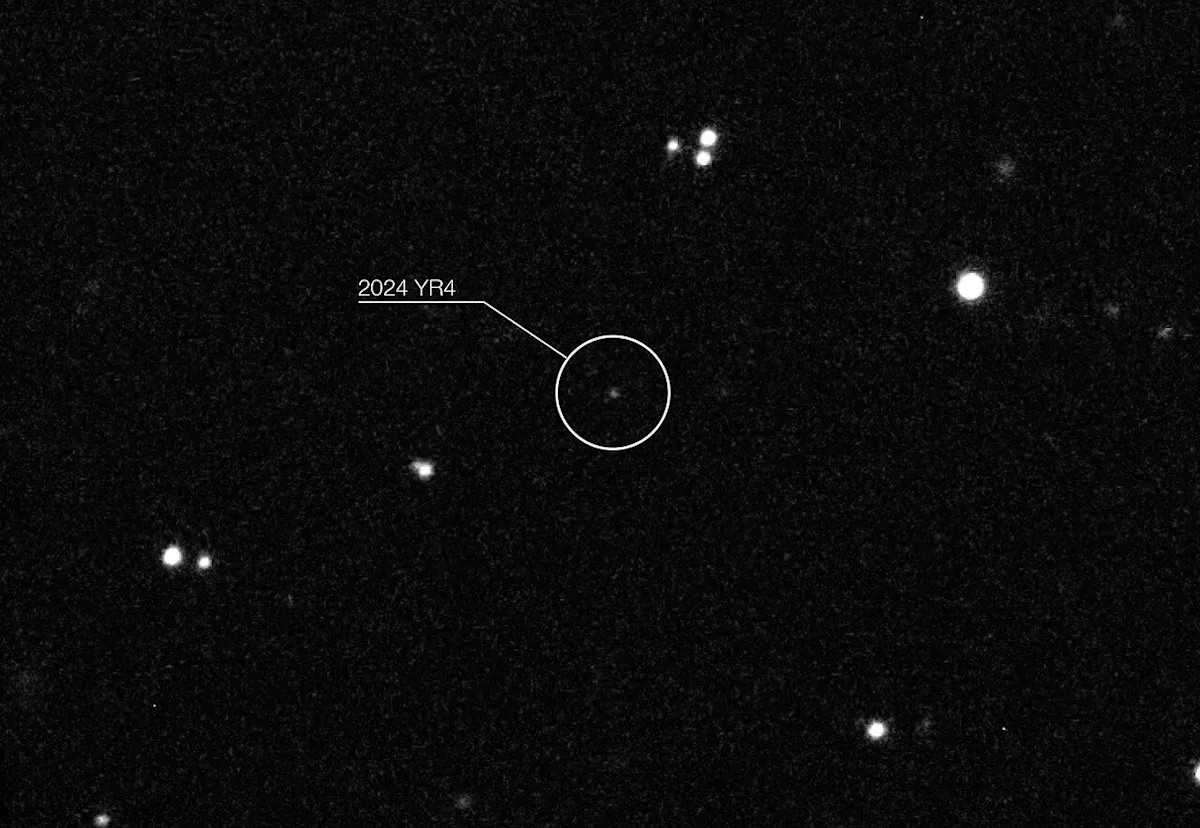

A recently discovered asteroid, designated 2024 YR4, has renewed debate over planetary defense—not for Earth, but for its lone satellite. While the risk of the rock ever hitting Earth has all but vanished, new orbital analyses suggest a nontrivial chance it might strike the Moon in 2032. That remote possibility has led some researchers to consider radical mitigation measures, including the controversial option of using nuclear devices to deflect or fragment the asteroid before impact.

The Changing Threat Landscape

When 2024 YR4 was first detected, early trajectory estimates hinted at a small but alarming chance of an Earth impact. That possibility has since been ruled out through refined observations and orbital modeling. However, recent data now place the Moon—and more specifically its surface—as a possible “target” of minimal odds.

Current models estimate roughly a 4 % chance that 2024 YR4 could collide with the Moon in December 2032. Although that probability may yet shift with further tracking, it has captured the attention of scientists for its potential secondary consequences.

A lunar impact by an asteroid of this size—a few tens of meters in diameter—would likely release substantial ejecta, sending rock and dust into space around the Moon. Some of that material could escape lunar gravity and travel into Earth’s vicinity. Models suggest that satellites, spacecraft, and even astronauts in low Earth orbit could face much higher fluxes of micrometeoroids for a period following the impact.

One study estimated that such an event could raise micrometeoroid exposure in Earth’s orbital space to levels comparable to a decade’s normal background, albeit briefly. The risk to satellites and fragile spacecraft surfaces would escalate, especially for those without shielding or capable of repositioning.

Options: Deflection vs. Destruction

Given the stakes, scientists are exploring two broad strategies: deflection or disruption.

1. Deflection (nudging)

- In theory, a spacecraft could rendezvous with 2024 YR4 and gently shift its trajectory—so it misses either the Moon or both Earth and Moon entirely.

- This is conceptually cleaner and less risky than blasting with a nuke, but its success depends critically on knowing the asteroid’s mass, structure, and internal cohesion with high precision.

- Because we have limited information on the asteroid’s density, composition, and structural integrity, any miscalculation risks pushing it in the “wrong direction,” possibly increasing the danger.

2. Disruption (fragmentation or destruction)

- If deflection proves infeasible—especially given the tight windows—some propose intentionally breaking the asteroid apart, or detonating a nuclear device near or on it.

- A well-placed nuclear explosion (a “standoff blast”) could scatter fragments small enough to miss the Moon or burn up harmlessly before reaching Earth’s orbit.

- However, fragmenting an asteroid carries its own dangers: some fragments might still be large and cross lunar or Earth orbit paths. Worse, the blast might impart momentum in unpredictable ways.

Proponents of the nuclear approach argue that if a Moon-impact becomes nearly certain and time is short, humanity should at least have the option on the table. Such arguments have sparked vigorous debate in aerospace and planetary defense circles.

Technical Challenges & Unknowns

Trying to deflect or destroy an asteroid is far more complex than it sounds. Among the core obstacles:

- Mass and density uncertainty: Without precise data on 2024 YR4’s mass and internal structure, any mission is planning in the dark.

- Timing constraints: Approaching the launch window too late could make deflection impossible or ineffective.

- Trajectory modeling precision: The asteroid’s path must be known with extreme fidelity to avoid accidentally setting up a future collision path.

- Fragmentation risk: Breaking the asteroid into pieces might still leave hazardous fragments. Some may retain trajectories toward the Moon or even Earth.

- Political, legal, and diplomatic dimensions: Using nuclear devices—even for planetary defense—raises treaty, global security, and regulatory challenges.

Given these uncertainties, many experts emphasize that early reconnaissance missions—to better characterize the asteroid—are essential before committing to drastic interventions.

The Strategic Case for Lunar Defense

It may seem odd to defend the Moon rather than Earth, but the Moon occupies “cis-lunar” space—regions between Earth and the Moon that include much of our satellite infrastructure. A lunar impact has unique cascading risks:

- Cloud of debris could threaten spacecraft and satellites in Earth orbit

- Temporary increases in micrometeoroid flux could damage instruments or degrade mission lifetimes

- Uncertainty and shock effects may impose new constraints on space operations

Thus, protecting the Moon also protects the broader near-Earth environment.

What Happens Next?

Over the next few years, the priority is clear:

- Observational campaigns to refine orbital parameters, mass estimates, and shape modeling

- Mission concept studies to assess feasibility, cost, and risk of deflector or interceptor craft

- International coordination to set protocols, treaties, and shared responsibility

- Simulations and testing of both deflection and disruption strategies under varying physical assumptions

If humanity acts early, a smaller “push” could be sufficient to avert the threat. If delayed, we may be racing against time with fewer safe options.

Final Thoughts

The asteroid 2024 YR4 may never strike the Moon—but even at a few percent likelihood, the potential consequences demand attention. Beyond the drama of “nuking space rocks,” this scenario touches on our ability to defend not just Earth, but the entire space environment we inhabit.

Preparing now—through better tracking, better mission design, and careful international planning—offers the best shot of keeping the Moon and Earth safe from cosmic collisions in the decades ahead.

Leave a Reply