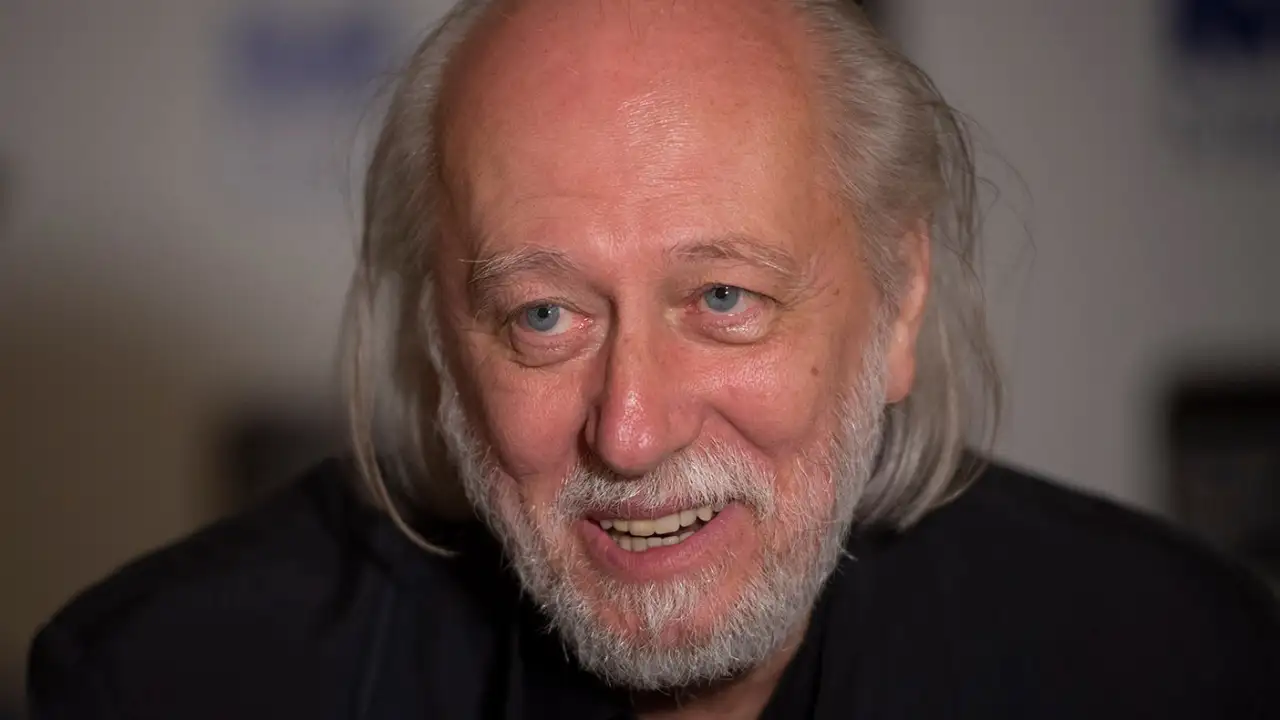

In a year defined by uncertainty and global upheaval, the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded to László Krasznahorkai, the Hungarian novelist whose dense, visionary prose has explored the fragile architecture of civilization and the relentless persistence of despair.

The Swedish Academy described Krasznahorkai as a writer of “apocalyptic imagination and spiritual precision,” honoring a body of work that illuminates “the dark currents of modern existence while revealing the faint light of human endurance.”

This recognition places Krasznahorkai among the most important literary figures of the postwar era, and marks a defining moment for contemporary European literature.

A Writer of Relentless Intensity

László Krasznahorkai, born in 1954 in the town of Gyula, Hungary, emerged in the 1980s as a radical new voice in Central European fiction. From his debut novel Sátántangó, first published in 1985, he has remained fiercely independent—rejecting easy storytelling and comfortable morality in favor of a prose style that feels like a fever dream stretched across endless sentences.

His novels often depict disintegrating towns, collapsing social orders, and individuals searching for meaning amid ruin. The worlds he builds are desolate yet strangely beautiful—echoing the landscapes of Kafka and Dostoevsky, but with a distinctive rhythm all his own.

Critics have called his prose “symphonic,” noting how his paragraphs stretch for pages, forming waves of thought and emotion that engulf the reader. Krasznahorkai’s writing invites readers not merely to read, but to endure, to surrender to language that vibrates with anxiety, devotion, and transcendence.

A Body of Work Born from Chaos

Krasznahorkai’s bibliography is compact yet monumental. His most celebrated works include Sátántangó, The Melancholy of Resistance, War and War, Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, and Seiobo There Below. Each offers a distinct yet interconnected vision of a world teetering on the edge of collapse.

In The Melancholy of Resistance, a mysterious traveling circus arrives in a decaying Hungarian town, unleashing a wave of disorder that reveals the fragility of authority and faith. Seiobo There Below, by contrast, turns eastward, weaving meditations on art, beauty, and eternity through scenes set in Japan, Greece, and Italy.

The Nobel Committee highlighted the “philosophical vastness” of Krasznahorkai’s work—his ability to blend European despair with a global awareness that transcends borders and ideologies.

The Filmmaker’s Collaborator

Krasznahorkai’s partnership with filmmaker Béla Tarr has become legendary. Together, they created a cinematic language as haunting and deliberate as the novels themselves. Sátántangó was adapted into a seven-hour film in 1994, regarded by many critics as one of the greatest achievements in modern cinema.

Their collaboration continued with Werckmeister Harmonies and The Turin Horse, both of which translate Krasznahorkai’s apocalyptic visions into long, hypnotic black-and-white sequences.

The fusion of literature and film elevated Krasznahorkai’s global reputation, making him an icon of what some critics call “slow art”—works that resist speed, noise, and superficial consumption in favor of silence, duration, and moral depth.

The Nobel Committee’s Decision

The 2025 award recognizes not only a single writer but a philosophy of literature that resists simplification. The Academy’s statement praised Krasznahorkai for his “formidable artistry and his refusal to accept the world as it is,” calling his novels “acts of moral resistance written in the face of despair.”

This year’s selection also carries political undertones. In an era marked by populism and the erosion of intellectual discourse, honoring a writer who champions complexity and introspection is a symbolic act of defiance.

It is the second time a Hungarian author has received the Nobel Prize in Literature, following Imre Kertész’s win in 2002 for his work on Holocaust memory and moral survival. Krasznahorkai’s victory, however, reflects a different preoccupation—one with metaphysical catastrophe rather than historical trauma.

A Voice Against the Void

Krasznahorkai’s fiction confronts the void—the spiritual emptiness of modernity—with a relentless gaze. His characters wander through desolate villages, decaying cities, and spiritual wastelands, searching for patterns in the chaos of existence.

While often labeled as “bleak,” his writing also carries a strange compassion. Beneath the despair lies a yearning for transcendence, a belief that art and consciousness still hold meaning even as the world disintegrates.

In War and War, for example, a lonely archivist believes he has found an ancient manuscript that must be preserved “for all of eternity.” The novel ends not with hope, but with a gesture toward endurance—the idea that even in ruins, the human mind continues to create.

That paradox—of despair entwined with devotion—is the essence of Krasznahorkai’s art.

Global Reaction and Literary Legacy

The announcement of the Nobel Prize was met with admiration from writers, critics, and readers around the world. Prominent authors hailed Krasznahorkai as “the last prophet of modern fiction,” while literary journals celebrated his influence on a generation of writers who embrace ambiguity and complexity over clarity.

Publishers across Europe and the United States have already announced new editions of his works, with fresh translations planned for multiple languages. University courses are expected to revisit his oeuvre, not only as literature but as philosophy—an exploration of the human condition in an age of entropy.

Hungary’s literary community reacted with both pride and poignancy. Some commentators noted that Krasznahorkai has often lived abroad and has been critical of his homeland’s political climate, yet his roots in Hungarian history and culture remain essential to his art.

Art as Endurance

Krasznahorkai once wrote that “the apocalypse has already arrived, only we do not yet understand it.” His novels reflect that sentiment—depicting a world that has ended but continues to move, a civilization that persists out of inertia, an artist who continues to write in defiance of meaninglessness.

By awarding him the Nobel Prize, the Academy acknowledges not only his literary genius but his moral vision: a belief that the act of writing itself is a form of survival.

His long, spiraling sentences—sometimes stretching across pages—are more than stylistic flourishes. They mimic the movement of thought, the rhythm of obsession, the persistence of being. Each word resists the collapse of order, pushing against silence with the weight of language.

Looking Forward

Krasznahorkai is expected to deliver his Nobel Lecture in Stockholm later this year. Literary observers anticipate a meditation not on success, but on solitude, duty, and the precarious state of art in a mechanized world.

For a writer who once described himself as “a chronicler of the end times,” this recognition may not change his outlook—but it ensures that his voice, forged in solitude and shadow, will echo across generations.

A Triumph of the Uncompromising

László Krasznahorkai’s Nobel win is not merely a celebration of literature; it is a statement about what literature can still be. In an era dominated by distraction and brevity, the world’s most prestigious literary prize has gone to a writer who demands time, patience, and humility.

His works remind us that meaning cannot always be simplified—that art’s task is not to soothe, but to awaken.

And so, as readers turn once more to the dense, hypnotic sentences of Sátántangó or The Melancholy of Resistance, they may discover in their pages not just darkness, but the stubborn light that endures when all else fades.

Leave a Reply