A newly announced international body proposed by U.S. President Donald Trump, known as the “Board of Peace,” is drawing global attention — and confusion — as invited world leaders attempt to understand how the unconventional initiative would actually function. While the White House has promoted the board as a bold mechanism to advance peace and reconstruction in conflict zones, many governments remain unsure about its structure, authority, and long-term purpose.

The Board of Peace is envisioned as a multinational group tasked with overseeing post-war governance, security arrangements, and reconstruction efforts, particularly in Gaza. According to officials familiar with the proposal, the board would coordinate political oversight, funding commitments, and security guarantees, operating alongside — or possibly outside — existing international institutions. However, key operational details, including voting rights, leadership roles, and legal authority, have yet to be clearly defined.

One of the most debated elements of the plan is its membership model. Countries willing to commit large financial contributions would reportedly gain permanent seats, while others could participate on a rotating or time-limited basis. This pay-to-participate structure has raised concerns among diplomats who argue that peacebuilding should not be determined by financial capacity alone. Critics warn that such a model could sideline smaller or less wealthy nations while amplifying the influence of major donors.

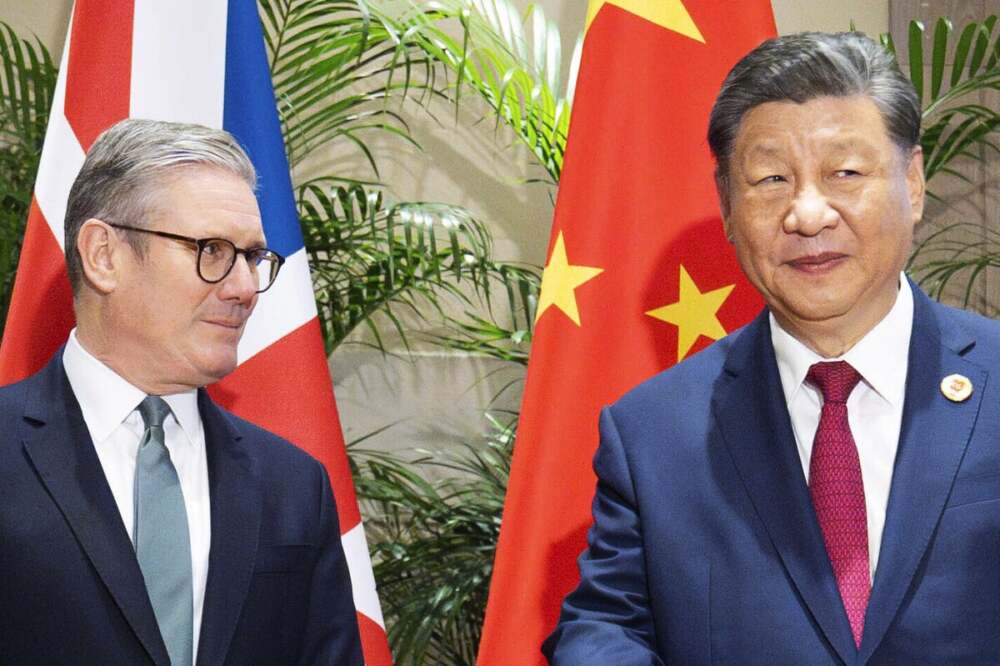

Reactions among invited countries have been mixed. Some governments have cautiously welcomed the idea, seeing it as an opportunity to shape post-conflict outcomes and gain diplomatic leverage. Others have responded with hesitation, privately expressing doubts about how the board would interact with existing frameworks such as the United Nations or regional peacekeeping mechanisms. Several European officials are said to be reviewing the proposal carefully, wary of endorsing an initiative that could weaken established multilateral norms.

Israel’s response has also been divided. While the invitation itself underscores the close relationship between Washington and Jerusalem, internal disagreements have surfaced within Israel’s political leadership. Some officials fear the board could impose external constraints on Israel’s security policy, while others see potential benefits in shared responsibility for Gaza’s future.

The inclusion of countries with sharply different geopolitical interests has further complicated the picture. Diplomatic observers note that bringing together nations with conflicting alliances and priorities could make consensus difficult, especially on sensitive issues such as disarmament, border control, and political authority in Gaza. Without clear rules for dispute resolution, the board risks becoming a forum for rivalry rather than cooperation.

Supporters of the initiative argue that traditional diplomatic approaches have failed to deliver lasting peace and that new structures are needed to break longstanding deadlocks. They view the Board of Peace as an attempt to inject momentum, resources, and accountability into stalled peace processes. The Trump administration has portrayed the plan as pragmatic rather than ideological, emphasizing results over protocol.

Still, many unanswered questions remain. Who would enforce the board’s decisions? How would it coordinate with humanitarian agencies and local authorities? And would its actions carry legal weight under international law? Until these issues are clarified, several invited leaders appear reluctant to fully commit.

As discussions continue behind closed doors, the Board of Peace stands at a crossroads. It could emerge as a transformative experiment in global diplomacy — or struggle to gain legitimacy amid skepticism and institutional overlap. For now, the initiative reflects both the ambition and the uncertainty that characterize efforts to reshape international peacebuilding in a rapidly changing world.

Leave a Reply