September 24, 2025

A major breakthrough in human genetics has come with the first complete sequence assemblies of Robertsonian chromosomes, revealing exactly where chromosome breakage and fusion occur in these common structural variants. The findings promise new insights into how such chromosomal rearrangements form, propagate, and influence health.

What Are Robertsonian Chromosomes?

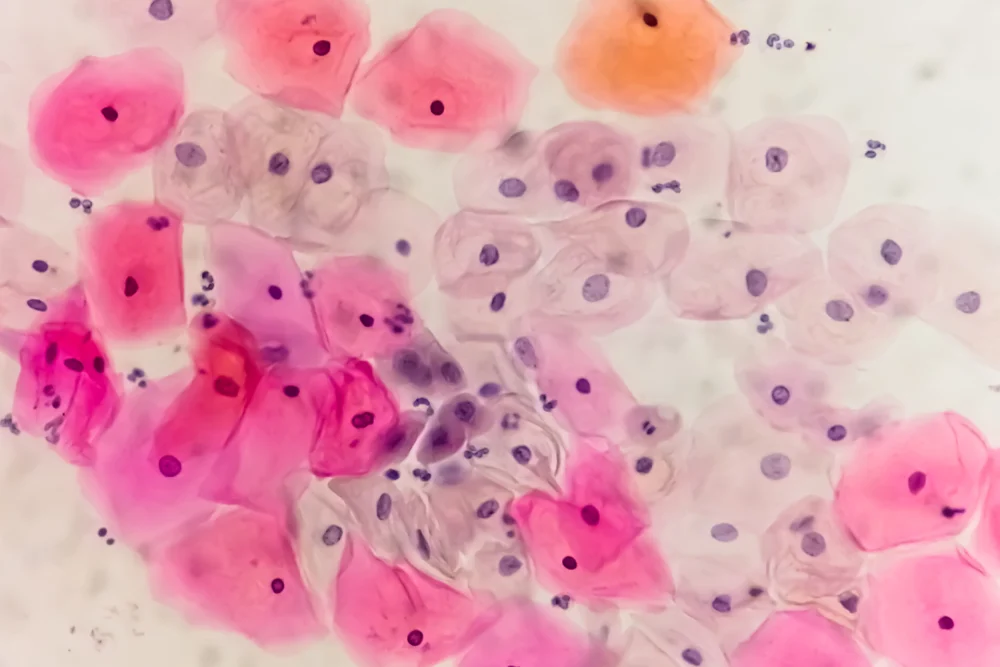

Robertsonian chromosomes are structural variants where two acrocentric chromosomes fuse together after their long arms break. This leads to a loss of their short arms and results in one fewer chromosome—carriers have 45 instead of 46 in those fused chromosomes. Though many carriers are healthy, these fusions can raise risks of infertility, miscarriages, and conditions like Down syndrome and certain cancers.

The Big Discovery

- Researchers fully sequenced three human Robertsonian chromosomes: two that fuse chromosome 13 with chromosome 14, and one that fuses chromosome 14 with chromosome 21.

- They located a common breakpoint—an area of genome breakage—within a region of repetitive DNA called SST1, a macrosatellite repeat found on chromosomes 13, 14, and 21. This region is now shown to be central to how these chromosomes fuse.

- The study also revealed that part of the structural arrangement making these fusions more likely is an inversion on chromosome 14—essentially a flipped region in SST1 compared to its orientation in chromosomes 13 and 21.

Stability and Epigenetic Control

One big question has been how fused chromosomes manage to behave stably under cell division, since they theoretically have two centromeres (the “anchor” points that attach to the spindle fibers during cell division). Key observations:

- In many fusions, though two centromeric regions are present, only one is “active”—silencing or epigenetic inactivation of the other helps avoid conflicting pulls during cell division.

- In some rare cases, both centromeres are active, but because they’re physically very close, cells use a single outer kinetochore structure—essentially coordinating them—in order to divide properly.

Implications for Genetics and Medicine

- Better understanding of reproductive risk: Knowing exactly how and where these fusions occur helps genetic counselors more accurately assess risks for carriers—for example, fertility issues or likelihood of producing offspring with chromosomal abnormalities.

- Evolutionary insights: The presence of repeated DNA sequences and structural features like inversions suggests a mechanism not only in humans but possibly across species. The study compared human data with that in chimpanzees and bonobos, finding that while SST1 repeats exist in those species, the specific inversion seen in human chromosome 14 appears unique.

- Genomic variation and “junk DNA” reconsidered: Regions once considered repetitive or non-functional—especially macrosatellite or non-coding repeat arrays—are revealed to play structural and perhaps regulatory roles in chromosome behavior and genome evolution.

What’s Next

Researchers plan to explore several follow-up questions:

- Do different individuals show variation in the size or orientation of SST1 repeats, and how might that influence the likelihood of Robertsonian fusion?

- What mechanisms enable the inactivation of one centromere in fused chromosomes, and can those be manipulated or predicted?

- Might similar fusion points exist in other, less well-studied types of chromosomal rearrangements?

- How do Robertsonian chromosomes behave over multiple generations, and what genetic or epigenetic factors influence whether they’re inherited or lost?

Final Thoughts

This study marks a landmark moment in cytogenetics: for the first time, the precise DNA breakpoint in common Robertsonian chromosomes has been mapped. That clarity helps fill in long-standing gaps about how chromosome fusions arise, how they avoid causing chaos in cell division, and how structural genomic variation influences both evolution and human disease.

Leave a Reply