For decades, neuroscientists believed that when a limb was amputated, the brain quickly reorganized itself, allowing nearby regions—such as those controlling the face or lips—to take over the area that once represented the missing hand or foot. A new study, however, has overturned that assumption, showing that the brain’s internal body map remains stable even years after amputation.

Phantom Movements Activate the Same Brain Regions

Using long-term brain scans of amputees, some followed for up to five years, researchers found that movements of phantom fingers or hands still triggered the same brain regions as before amputation. This surprising result suggests that the brain doesn’t “erase” or “remap” missing body parts. Instead, the representation of the limb persists, as if the brain is holding on to a memory of what once was.

Explaining Why Some Therapies Fail

This discovery could explain why certain treatments for phantom limb pain—such as mirror therapy or virtual reality exercises—often provide only limited relief. These therapies are built on the assumption that the brain’s map must be restructured. If the map is actually intact, the root cause may lie elsewhere.

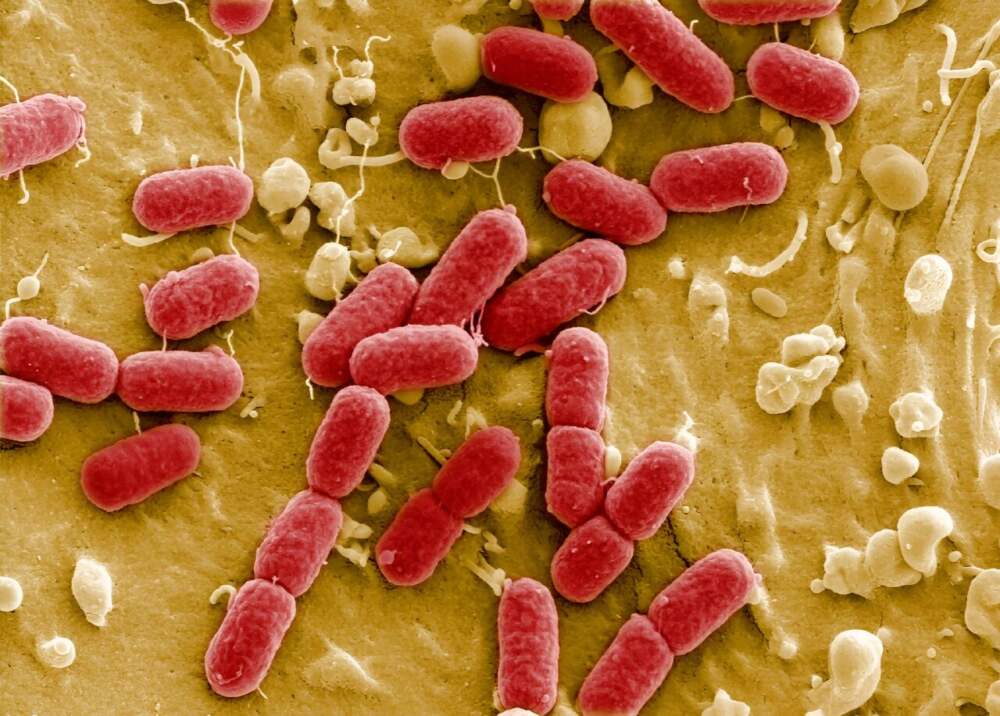

The Role of Nerves, Not the Brain

Evidence now points to damaged nerve endings at the site of amputation as a likely source of phantom limb sensations. When severed nerves misfire or form tangled clusters, they can send confusing signals to the brain, producing the illusion of pain or movement in a missing limb.

A New Future for Prosthetics

Perhaps the most promising outcome of this research lies in prosthetic development. Because the brain’s representation of the limb remains unchanged, engineers and neuroscientists can design prosthetic devices that tap directly into these existing pathways. This could allow amputees not only to move artificial limbs with greater precision but also to potentially restore sensations such as pressure, texture, or even temperature.

Why This Matters

- Challenges a decades-old assumption about brain plasticity.

- Offers new insight into why phantom limb therapies often fail.

- Shifts focus from retraining the brain to treating damaged nerves.

- Opens exciting opportunities for next-generation prosthetics and brain-computer interfaces.

Leave a Reply