When Francisco Franco died on November 20, 1975, many in Spain hoped that his death would finally close a dark chapter in their history. Yet, half a century later, the country is still wrestling with the deep scars left by his nearly forty-year dictatorship. The legacy of Franco is not just in textbooks or museums — it lingers in mass graves, in political debates, and even in the social attitudes of a new generation.

Unearthing the Past: Mass Graves and the Quest for Memory

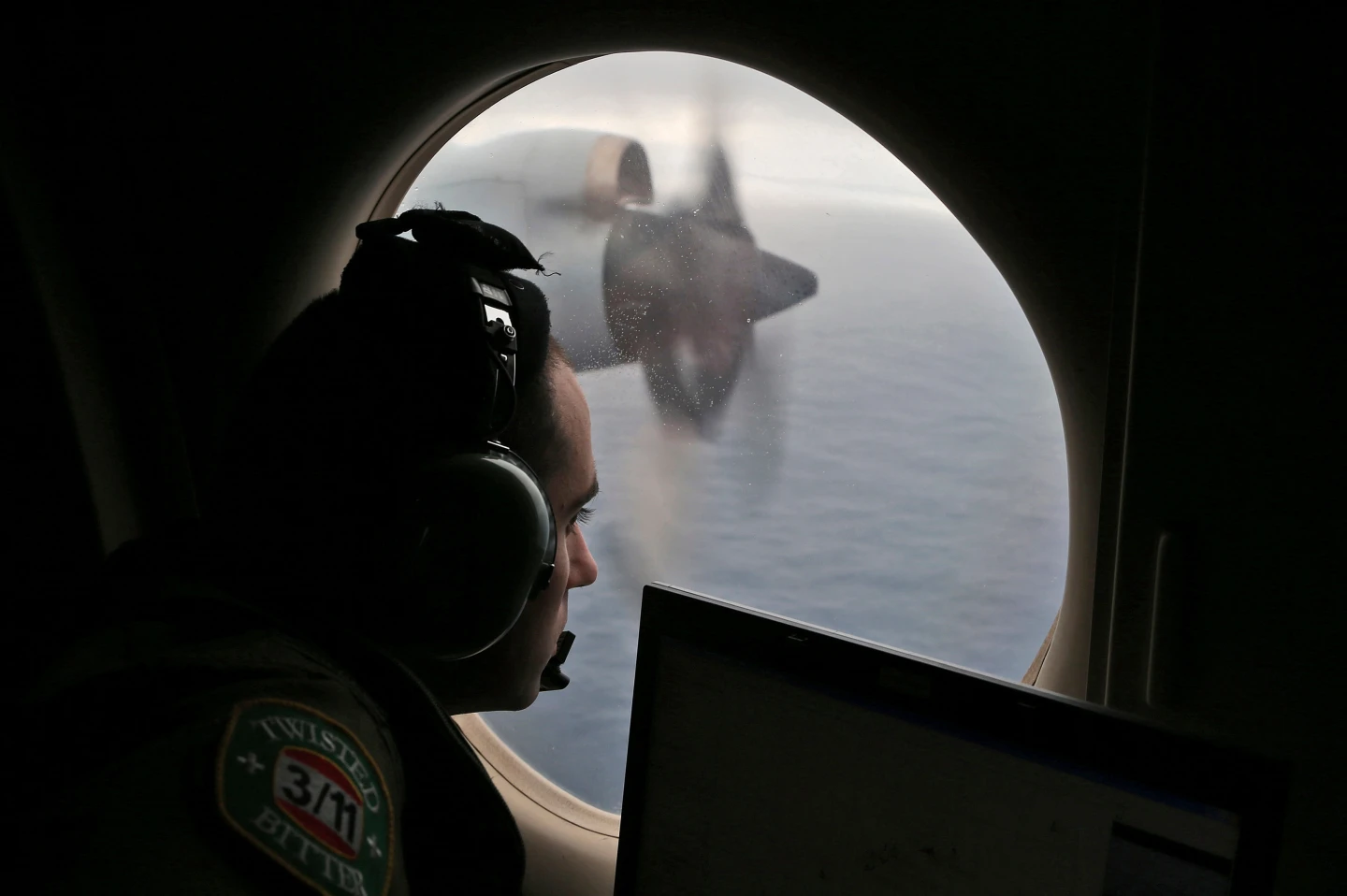

One of the most tangible reminders of Franco’s brutal rule is the thousands of unmarked mass graves scattered across the Spanish countryside. For decades, these graves stayed hidden — in forests, abandoned cemeteries, remote hills — symbolic of a national silence that followed Franco’s death. Today, thanks to renewed exhumation efforts, many families are finally confronting that silence. For them, recovering the remains of loved ones is not just about history — it is deeply personal, a way to heal wounds that were never officially acknowledged.

But the process is fraught with challenges. Archaeologists and forensic teams face logistical, financial, and bureaucratic hurdles, and in many cases the identification of remains is complicated by decades of decay and limited records. Yet, for those who press on, each exhumation is a step toward closure, a reclamation of dignity for victims once buried in anonymity.

Laws of Remembrance: The Democratic Memory Law

To address these painful legacies, the Spanish government passed a sweeping “Democratic Memory” law in 2022. This legislation is more than symbolic: it creates a national registry of victims, establishes a DNA bank to help identify bodies from mass graves, and mandates the removal of Francoist symbols from public life.

Perhaps most significantly, the law calls for a redefinition of the mausoleum known as the Valley of the Fallen, where Franco himself was buried for decades. The site has been renamed and transformed into a “place of memory” rather than a shrine. Former noble titles granted by the Franco regime are being abolished, and organizations that glorify the dictator are being disbanded.

These reforms reflect a broader effort to institutionalize memory — not just to remember, but to educate and to reconcile.

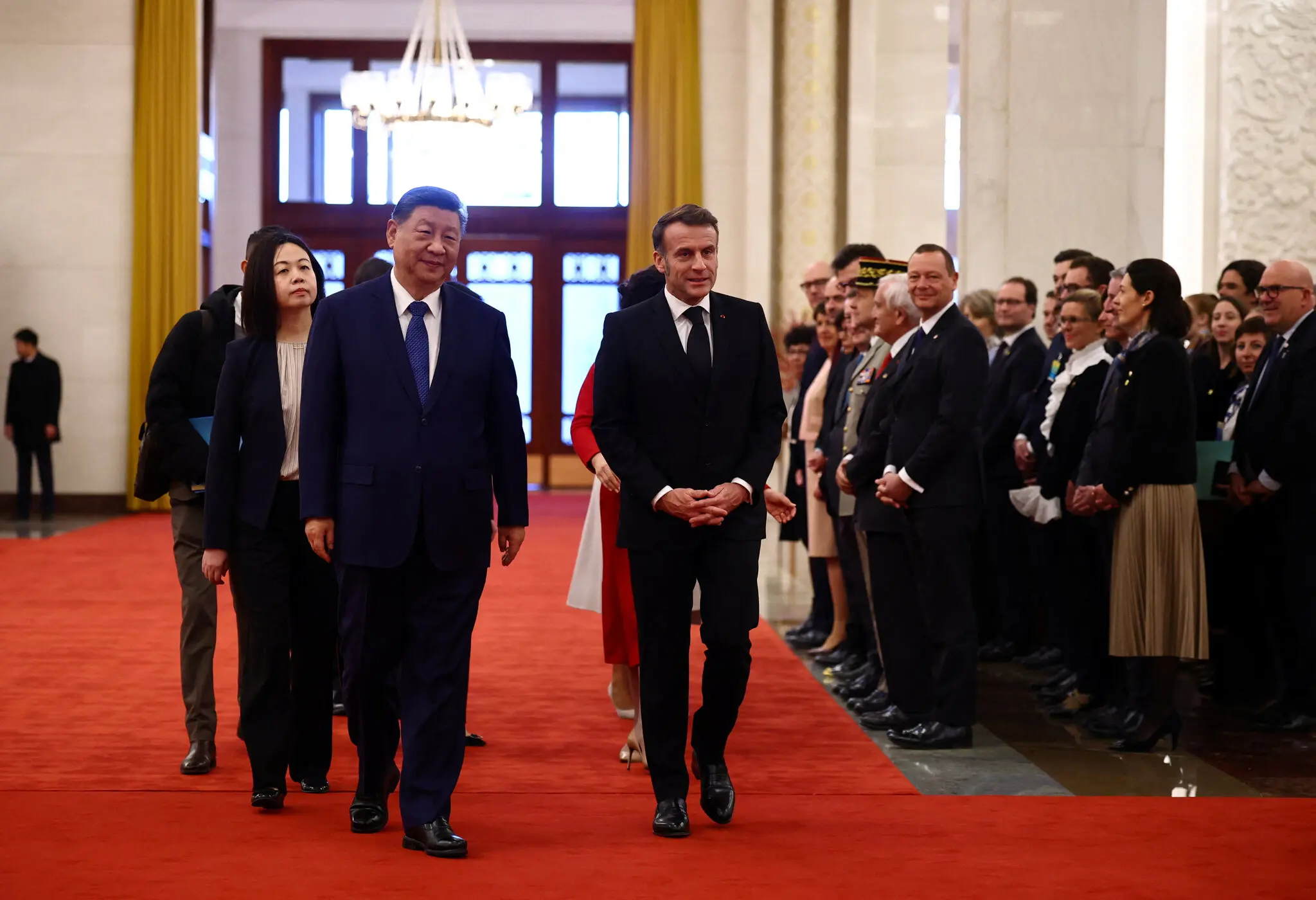

A Fragile Reconciliation: The Politics of Memory

Despite state efforts, Spain remains deeply divided over how to commemorate Franco’s legacy. The “Pact of Forgetting,” a political compromise from the early years of Spain’s transition to democracy, granted amnesty for many crimes committed under Franco. That pact prevented prosecutions and allowed the country to transition more smoothly, but it also left many victims without justice.

Critics argue that the 1977 Amnesty Law, still technically in force, continues to block deeper accountability. Although the Democratic Memory Law represents major progress, some believe it does not go far enough: ongoing impunity for historical crimes and the absence of full reparations remain contentious issues.

Moreover, the political responses to memory are polarized. The left, particularly the current government, has pushed for a full reckoning with the past as part of defending democratic values. On the right, some argue that the focus on historical memory is politically motivated, and far-right parties have resisted many of the reforms. Some of these divisions are not just political — they are generational.

Nostalgia Among Youth: A Worrying Trend

Perhaps the most surprising — and disturbing — dimension of Franco’s legacy is the revival of pro-Franco sentiment among some younger Spaniards. Many of today’s 18- to 30-year-olds never experienced the dictatorship. Yet a portion of this generation expresses a favorable view of Franco’s era, influenced in part by romanticized narratives on social media.

For some young people, nostalgia for Franco is less about ideology and more about disillusionment: economic insecurity, mistrust in institutions, and a feeling that democracy has failed them. The image of Franco’s Spain as orderly and stable — however distorted — can seem alluring in contrast to contemporary political and social turbulence.

Educators and historians are alarmed. They warn that this revival of authoritarian mythologizing reflects a gap in collective memory and education, and could fuel political polarization in the future.

Commemoration without Consensus

As Spain marks the 50th anniversary of Franco’s death, official commemorations have become sites of contention. The government’s centennial program is framed around “50 Years of Freedom,” but its narrative is not universally accepted. Right-wing parties have boycotted some of the events, arguing that they are partisan, while organizations nostalgic for Franco have held their own gatherings.

At the same time, victims’ groups continue to press for recognition. Families who lost loved ones during the civil war and dictatorship are pushing for more exhumations, better archival access, and stronger reparations. For them, memory is not just a matter of politics — it is a moral imperative.

How Spain Has Changed — and What Remains Unresolved

There is no denying that Spain has transformed profoundly since 1975. The constitution of 1978 enshrined democracy, civil liberties, and a modern state. Women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and freedom of speech have expanded dramatically. Economically, Spain has become integrated into the European mainstream, and politically it has shifted from authoritarianism to pluralism.

Yet, the legacy of Franco continues to cast a long shadow. The absence of criminal trials, the slow pace of exhumations, and the enduring divide in how his era is remembered highlight how many of the dictatorship’s traumas remain unhealed.

The challenge for Spain today is not just how to remember, but how to learn — how to build a shared narrative that acknowledges suffering without erasing the complexity of history. It is a struggle to ensure that memory does not just become a tool of political mobilization, but a foundation for democratic resilience.

The Road Ahead: Memory as a Democratic Project

Fifty years after Franco’s death, Spain is engaged in a delicate balancing act. The state’s commitment to exhuming mass graves, educating future generations, and removing authoritarian symbols signals a desire to institutionalize memory. But this project of remembrance must navigate deeply rooted divisions: legal inertia, political resistance, and generational gaps.

Ultimately, the effort to confront Franco’s legacy is not a purely historical exercise — it is a test of Spain’s democratic maturity. Can a society truly reckon with its darkest chapters without falling into polarization? Can memory be a force for unity, rather than division? The answer will shape Spain’s future as much as its past.

Leave a Reply