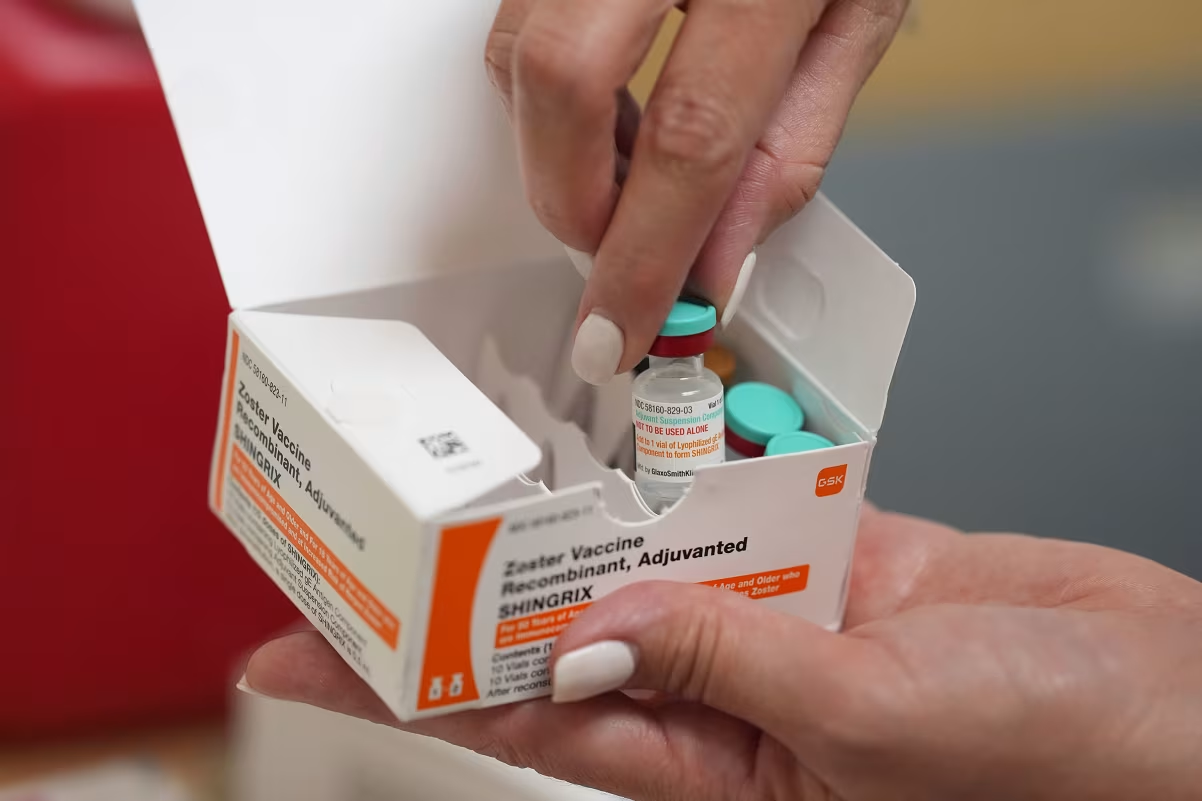

A major shift in American vaccine policy is under debate as federal health advisers appointed under Robert F. Kennedy Jr. weigh whether to eliminate the long-standing recommendation that all newborns in the United States receive the hepatitis B vaccine at birth. The proposal marks one of the most consequential changes to childhood immunization guidelines in decades and has sparked intense discussion among medical experts, public health officials, and parents.

The advisory group is considering limiting the birth-dose hepatitis B vaccine only to infants born to mothers who test positive for the virus. Under this approach, most newborns would no longer receive the vaccine automatically. Instead, parents would decide whether to vaccinate later, typically starting around two months of age. Additional doses might also require antibody testing beforehand, which would significantly alter the current three-shot routine given to nearly all infants.

The hepatitis B vaccine has been a cornerstone of U.S. childhood immunization since the early 1990s. The existing policy has contributed to a dramatic decline in hepatitis B infections among children, particularly those at highest risk. Hepatitis B is a potentially serious virus that can cause chronic liver disease and cancer, especially when contracted during infancy.

Supporters of the proposed change argue that universal birth vaccination may no longer be necessary in lower-risk settings and emphasize the importance of parental autonomy. They contend that a risk-based approach focusing specifically on infants of infected mothers would still prevent the most dangerous cases while giving families more decision-making power.

However, many pediatricians and public health experts warn that reversing the universal recommendation could lead to a resurgence of infections. They note that not all pregnant women receive timely hepatitis B screening, and some contract the virus late in pregnancy. The birth-dose vaccine has long served as a safety net for these gaps in testing. Critics caution that removing automatic protection may leave thousands of infants vulnerable each year and could reverse decades of progress in controlling the disease.

The debate comes as the advisory committee undergoes major changes, with several new members skeptical of long-standing vaccine policies. The decision, when finalized, is expected to influence not only medical practice but also public confidence in childhood immunization as a whole.

As the country awaits the committee’s ruling, the discussion over the hepatitis B vaccine highlights the broader national conversation about science, trust, and parental choice in healthcare.

Leave a Reply